Charles Dickens was very much a man of his time. Much of his fiction (almost all) was inspired by the world around him: specifically, the plight of the London poor. One of his most famous works (which happens to be a favorite of mine!), A Christmas Carol, was partly inspired by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several homes for London’s destitute children. He famously used to take long walks alone, all around London, and observe the world around him, getting inspiration for his books. Dickens and his characters – Oliver Twist, Ebenezer Scrooge, David Copperfield etc. – are basically synonymous with 19th century London. Which is why I think it’s so interesting that one of his most famous novels – A Tale of Two Cities – isn’t set in Dickens’ familiar stomping ground, but rather in the late 18th century, during the French Revolution and The Terror.

A Tale of Two Cities is a work of historical fiction, and it takes place between London and Paris (those are the titular ‘two cities’) in the 1780’s and 90’s. I was drawn to it because I love A Christmas Carol (the book) and also because I was curious to see what Dickens, a man writing in the 1850’s, had to say about the late 18th century. The equivalent would be someone now writing about the 1960’s. There’s still a removal of time, but a much smaller one than if it were me or you writing about the 18th century.

A Tale of Two Cities is also considered a ‘classic’ and while I think that one shouldn’t feel any pressure to read any book simply because it’s well-known and famous – that goes for ‘classic’ as well as contemporary lit – I do think Dickens (like Shakespeare) is an author whose work has endured for a reason. Or several. One reason, I think, is that Dickens (again, like Shakespeare) can be read on two levels – for entertainment value (if you purely want a rollicking good read!) and also on a more analytical, thematic level. His books are amusing but also rich and thought-provoking. He’s a bit over-the-top sometimes, but he also writes with so much empathy and with close observation of humor behavior. And his outage at societal inequalities is sadly still quite relevant, just as it was in the 19th century.

So now you know what I think of Dickens generally, but how was A Tale of Two Cities specificially? A ‘classic’ worth checking out, or one to skip?

Overall, I really liked this novel. No surprise, because I like Dickens’ writing and I like the 18th century (as you know!). But there’s a lot to like here even if you aren’t crazy about either of those things.

It tells the story of one family that is caught up in the events of the French Revolution, and it asks a lot of questions about justice and guilt. One man is basically asked to pay for the crimes committed by his cruel, aristocratic family on the Parisian poor. He has rejected his family long ago and deplores their actions, but the revolution is imminent and the oppressed want blood. How do we make amends, when our ancestors and sometimes even our close relatives, have committed atrocities or acts of oppression? And how far is ‘too far’ when it comes to gaining justice and retribution for the crimes of the past?

These questions are always interesting and I think they’re especially interesting in Dickens’ hands because this is a man who really fought for the rights of the London poor and has a clear empathy for the oppressed French poor and makes it clear why they revolted. We see that, to certain aristocratic nobles, these poor people’s lives are meaningless and expendable A boy is crushed to death under a nobleman’s cart wheel and the noble doesn’t bat an eye. A noble looks down at one of his tenant farmers, on the verge of death, ‘as if he were a wounded bird, or hare, or rabbit; not at all as if he were a fellow creature.’

Yet Dickens also condemns the violence of the Revolution fairly explicitly. The primary antagonist of the story, the sinister Madame Defarge, is an embodiment of the Revolutionaries’ desire for revenge and for heads to roll (quite literally). She is a ‘ruthless woman’ with an ‘inveterate hated of a class’ which has turned her into a ‘tigeress.’ She’s violent, excessive and without mercy, but we do see why she’s this way and how she personally has been abused by members of the upper class. So her behavior is, at least, understandable. It’s this keen sense of specifically class-based oppression throughout that makes Dickens a good writer for this subject, because he’s quite ambivalent – the violence is reprehensible, but he gets why it happened. And he’s aware that it could happen again.

Crush humanity out of shape once more, under similar hammers, and it will twist itself into the same tortured forms.

One of my favorite things about the book was Dickens’ descriptions of people. No surprise, the characters were super vivid and easy to visualize, down to the smallest player. A random jailer is described as: ‘so unwholesomely bloated, both in face and person, as to look like a man who had been drowned and filled with water.’ And all of the main characters are vivid, and relatively complex, except one: Lucie Manette. She’s worse than Mina in Dracula. She has no personality or life outside of her self-sacrificing devotion to her husband and father. Dickens seems to have no interest in either her bodily or intellectual reality – she has a child and it grows to the age of a toddler in the space of about a paragraph or two. (How do these events change her?!) She’s gorgeous, everyone loves her and would do anything for her – in short, she’s a very silly and unexamined character. With another author I’d let it slide but there’s no excuse for it when Dickens can create a character like Sydney Carton – the sarcastic, drunken, intelligent, self-loathing, spiteful yet surprisingly tender character who plays a central role in the novel’s climax.

Sydney Carton is great and, quite frankly, the whole book is pretty great too. It asks if a man, a family, even a society, can be redeemed. It isn’t spoiling much to say that, for Dickens, the answer is yes. I’m a bit more cynical, but even so, it’s nice to hope.

It would be perfect reading if you enjoy things like Poldark, or other dramas set in this period revolving around one family. I cried a lot at the end of the book, actually. Dickens can be a bit melodramatic, but his earnestness gets me every time.

Let me know what you think of A Tale of Two Cities: have you read it before? Did you read it in school? Do you plan on reading it in the future? I’d love to have any reading recommendations from you as well, particularly any spookier books as autumn approaches!

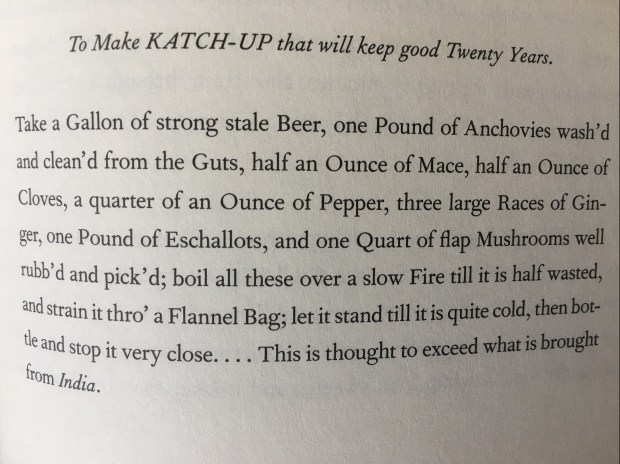

PS Today’s Featured Image is ‘Bonaparte aux Tuileries – 10 August 1792’, a painting depicting Napoleon (who would later become Emperor of France) witnessing a mob attack on the Tuileries Palace.

‘Madeira Mondays’ is a series of blog posts exploring 18th century history and historical fiction. Follow the blog for a new post every Monday and thanks for reading!