When we think of historical fiction, we tend to think about novels. It seems like a collective decision was made, somewhere down the line, that fiction set in the past should be EPIC in its scope. That historical tales were best suited to sprawling tomes with many sequels. Now, don’t get me wrong. I love a good historical novel (I’m writing one as we speak!). And I understand the appeal of getting wholly immersed in another time period, which one can do with a novel: learning about the minutia of life, meeting a big cast of characters, covering several years etc. BUT there is also something to be said for the short story as a medium for exploring history too.

Why are short stories such a brilliant form for historical fiction?

Well, for one thing, they reflect the way that the past often comes to us, which is in brief, fragmented, incomplete bursts. An old photograph discovered in an attic. A torn out page from a diary. Pieces of historical evidence often provide tiny windows to another world, but so much is left unknowable. Similarly, short stories are tiny windows into another world. A brief flash, a glimpse, but with much that you have to fill in and guess for yourself.

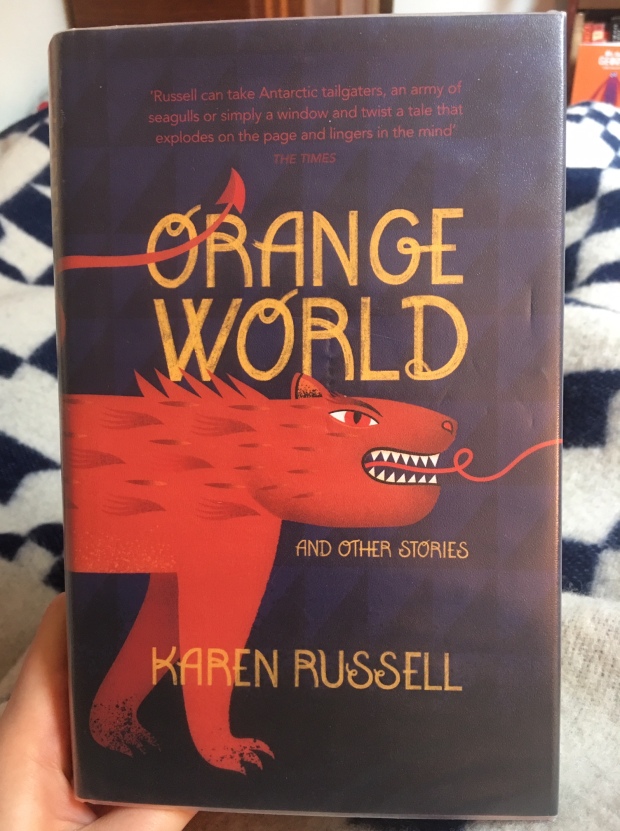

Also, maybe I am greedy, but sometimes I would rather read a collection with many different settings and characters, rather than commit to a whole book with just one time period and one setting. Enter Karen Russell. One of my absolute favorite writers. She writes both short stories and novels and many of her stories take place in the past – whether that is the old American West, 17th century Greece, or 19thcentury Japan. Lots of her stories are set in the present too. But all of her tales have fantastical or magical realism elements to them and they are all ridiculously well written. I actually feel wiser after reading her stories, like I have understood something new about human nature. Or, at least, have recognized something that I had not thought about before.

I was so excited to read her new collection last week – Orange World – and it exceeded my (very high!) expectations. So, for today’s ‘Madeira Mondays’, I wanted to point you towards some of my favorite, historical fiction stories by Karen Russell! Even though, regrettably, none of her short stories are set in 18th century America (Please write a story set in 18th century America, Karen! Please!!), lots of them explore other periods of American history and the American landscape. Here are four of her stories that I recommend reading ASAP.

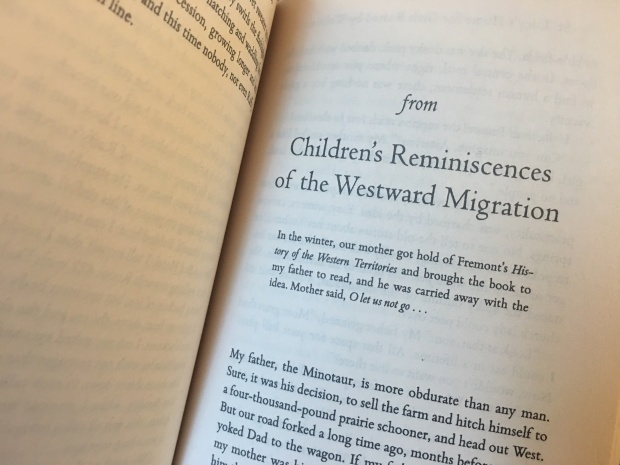

1 – ‘from Children’s Reminiscences of the Westward Migration‘, in St Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves

Russell is an American writer originally from Florida, and many of the stories in her first collection, St Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, take place in a weird, heightened version of a Florida swamp. But she’s also clearly interested in the landscape of the American West and one of my favorite stories from that collection is titled: ‘from Children’s Reminiscences of the Westward Migration‘. The title suggests a historical document, that the story we’re about to read is one from a larger collection of children looking back on their experience moving out west. But this expectation is playfully subverted in the very first line when we release that our boy narrator has a father who is a MINOTAUR. Yup. A Minotaur. Half-man, half-bull.

Thus begins a story that is really about myths: the myth of the American West (versus the harsh reality of life there), the myth of the Minotaur, the myth of this particular Minotaur character who, our narrator tells us, was once a famous rodeo star, AND about how parents seem like myths to their children, until we start to see their flaws.

You can hear Russell reading the beginning of the story here, to see if it might be your cup of tea!

2 – ‘Proving Up’ from Vampires in the Lemon Grove

Russell’s second collection, Vampires in the Lemon Grove, is my personal favorite and there’s another story about the American West in it, although this one is much darker than ‘Westward Migration’. It is about the rapacious desire for land and ownership, and this dark greed manifests itself as a very dark force that threatens the characters, who are settlers on the American frontier. The ending is so sinister it took my breath away! Apparently it has also been turned into an opera.

3 – ‘The Barn at the End of Our Term’ from Vampires in the Lemon Grove

This is a goofy story which is dear to my heart, about US Presidents reincarnated as horses. Yes. Horses.

I actually wrote about it for part of my PhD thesis, which looked at different iterations of John Adams in fiction, because Adams the horse is a central character in the story. He tries to lead the other Presidents-turned-horses to rebel and break out of the barn. Sure, it’s a silly and fun concept, but it’s really about legacy and what kind of ‘afterlife’ these Presidents have in our imaginations. So it’s not so much ‘historical fiction’ as fiction ABOUT history. It’s also funny as hell and insightful.

4 – ‘Black Corfu’ from Orange World and other stories

Okay, so this story is definitely historical, but not set in America. The setting is the island of Corfu, 1620. I included it on this list because it is my favorite story from her latest collection and I’ve read it twice already. This story is about an ambitious, intellectual physician whose job it is to cut the hamstrings of corpses so that they do not rise from the dead and become zombies. He once aspired to be a great doctor, but his dark skin color and his class have prevented him from rising in his profession. When rumors start to spread that a dead woman has been seen roaming the island, the doctor is blamed and chaos ensues.

This story, like all of her stories, is about many things at once. Its themes are super relevant to us today, although they are explored in a historical context: class, race, science, superstition, ambition and the power of fear.

*

Have I convinced you to read her yet? I hope so! And I hope that you will enjoy these strange historical stories as much as I do.

Recommended Reading:

Orange World and Other Stories; Vampires in the Lemon Grove and St Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves by Karen Russell (obviously!)

Voices Against the Wall: The Hilarious Terror of Karen Russell’s “Orange World and Other Stories” (in-depth review of Orange World and other stories) from the LA Times

‘Bog Girl’ by Karen Russell in The New Yorker (also featured in Orange World)

‘Madeira Mondays’ is a series of blog posts exploring Early American history and historical fiction. I’m not a historian, but an author and poet who is endlessly fascinated by this time period. I am also currently writing/researching a novel set during the American Revolution and recently finished a Doctorate of Fine Art looking at how creative writers access America’s eighteenth-century past. Follow the blog for a new post every Monday and thanks for reading!