Who was Sally Hemings?

One short, and incomplete, answer is that she was Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved mistress, with whom he fathered several children. But of course Sally Hemings was much more than that one fact. As it says on the website for Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, she was a ‘Daughter, mother, sister, aunt. Inherited as property. Seamstress. World traveler. Enslaved woman…Liberator. Mystery.’ The page goes on to describe her as ‘one of the most famous-and least known-African American women in US history’.

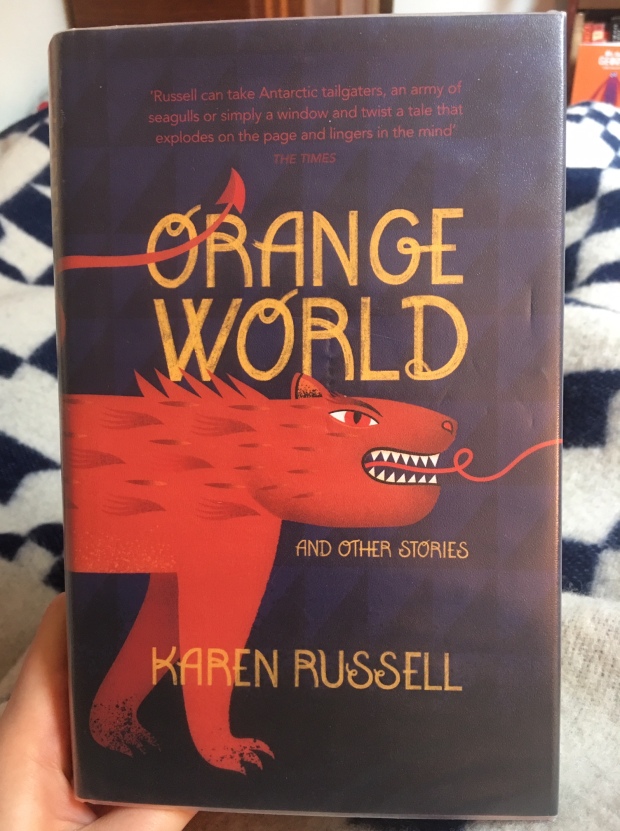

Thomas Jefferson’s home Monticello in Virginia. Taken during my fellowship there in 2016.

Although I’d heard her name before, I first learned about Sally’s story during my residential fellowship at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello three years ago. When I was living there in Summer 2016, they had not yet set up the new exhibition displaying some of Hemings’ artifacts, in what would have been her living quarters, but I still learned about her through the Slavery at Monticello Tour and even more so through another fellow who was also living at Monticello at the time: author Chet’la Sebree.

Chet’la was at Monticello researching a collection of poetry inspired by Sally’s life. Chet’la’s work would imaginatively explore and grapple with Sally’s internal struggles and deliberations, her loves and losses, the complex nature of her relationship with Jefferson. In doing so, these poems would imbue this often missing or maligned historical figure with something of the multi-dimensional humanity the real, historical Sally had in life. The poems that Chet’la was working on would eventually become part of her debut collection, Mistress, released last month from New Issues Press.

Having just finished reading Mistress, I can recommend it for several reasons (and not just because Chet’la is a friend!). Firstly, this book really brings to life the internal and external world of Sally Hemings. It is absolutely crackling with vivid historical details that evoke the lost, material world that Sally lived in. In ‘Dusky Sally, February 1817’, the persona of Sally reflects:

In star-latticed sky, I hear my niece’s cries, feel my mother’s hand on

my fire-warm face, smell the lavender she used in her vase, taste

everything James once made: fried potatoes, pasta with cheese, ice

cream. (…)

The collection dramatizes and imagines Sally’s internal life as well, in a way that traditional non-fiction history could not do. Sally did not leave any diaries or written accounts in the first person, and much of what we know about her comes to us from her son Madison Hemings (who was freed in Jefferson’s will and ended up in Ohio where he owned a farm). So we are left to imagine how she might have felt as her eventful life unfolded.

The kitchens at Monticello

Perhaps most significantly, Mistress explores her conflicted feelings about returning to Monticello from Paris. In the late 1780’s, Sally went to Paris to be Jefferson’s daughter’s maid, and it was there that she began a sexual relationship with Jefferson. Slavery was illegal in France, so she could have stayed on there and remained free, but she chose to return to Virginia with Jefferson and to her life of slavery. In return, she was promised ‘extraordinary privileges’ at Monticello and that her children would be freed. But why did she return? Did she ever regret that choice? These are things that we can never know, but through Sebree’s rendering of Sally’s life, we can picture her grappling with this choice and many others. We see her back at Monticello, circling a fishpond, ‘thick summer wind/prickling fair hair on skin’, pacing and ‘wonder(ing) if my decision was right.’

But, crucially, the persona of Sally is not the only voice that we meet in Mistress. Sally’s imagined voice is in dialogue with a contemporary speaker (or perhaps several speakers) who reflect on their experiences of sex, relationships and racism in modern America. At times this modern voice explores the erasure of black female sexuality, in particular in the poem ‘At a Dinner Party for White (Wo)men’. This poem is a response to Judy Chicago’s art exhibition The Dinner Party (1979) in which the only black woman featured in the exhibit, Sojourner Truth, is (as Sebree explains in the end notes) ‘rendered without a vagina: she is instead, depicted by three faces.’ The poem begins:

Everyone else is invited to meet their vaginas-

different denominations and colors-

except me, the magical negress. My box

always absent because desire is not a privilege

for disenfranchised women

descendant from slaves-

we, still, their dark continent.

At times the poems also delve into the hyper sexualization of black women, reflecting on how in Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex (1972) the term for rear-entry intercourse is sex ‘a la negresse.’ The modern black speaker is conflicted by her own sexual desires (‘I stifle myself, pretend I don’t/love shower sex a la negresse’) and is worried that her sexual partner might see her only as ‘kinks to get lost in’, instead of an individual. The poem I have just quoted from, ‘Dispatches from the Dark Continent’, follows a poem called ‘Paper Epithets, December 1802’ which is told in Sally’s voice. ‘Paper Epithets’ lists out some of the pejorative terms that were used to described Sally in newspapers, after her relationship with Jefferson became public knowledge: ‘an instrument of Cupid’ ‘yellow strumpet’ ‘wench Sally’. But, Sally says in the poem’s powerful final line, she is always described in reductive ways, but she is never seen as ‘the woman that I am.’

By positioning these two poems next to each other, ‘Dark Continent’ and ‘Paper Epithets’, we see a parallel emerging between these two personas, past and present. We see how they are both reduced in the eyes of others – whether a contemporary lover or turn of the century journalists – to so much less than what they really are. Throughout the collection, these two voices, contemporary and historical, are always in dialogue with each other. We come to see how racism, and in particular degrading attitudes towards black female sexuality, lives on in modern America. Towards the start of the book, Chet’la quotes from historian Annette Gordon-Reed who writes: ‘The portrayal of black female sexuality as inherently degraded is a product of slavery and white supremacy, and it lives on as one of slavery’s chief legacies and one of white supremacy’s continuing projects.’

The gardens at Monticello where enslaved people would have labored.

Mistress is the sort of book that you could read in one or two sittings, getting immersed in the sensuous and troubling worlds of the various, intermingling speakers. OR you could return to it again and again with a ‘scholarly’ eye and see how Sebree has used the various, often sparse, facts of Sally’s life to shape Mistress. There is a timeline provided at the back and you could easily spend time seeing where each poem fits into that timeline, what historical events are being referenced or alluded to. There are also detailed Notes where you can learn more about what works of art or historical materials are being referenced in each of the poems. This is a book that is layered with allusions to other texts.

This is also a book that deeply understands the limitations of the ‘persona poem’ (a literary term for poems that adopt the voice of a speaker who is not one’s self) and how Sally Hemings cannot ever truly be understood or rendered by a modern writer. Sebree acknowledges this, yet this book is still a powerful resurrection of a historical figure. In many ways, it is a restoration of the humanity that Sally Hemings was denied both in life, as an enslaved woman, and in history, as someone who was often reduced to nothing more than a pejorative epithet by her contemporaries or ignored entirely by some modern historians. The story of Sally Hemings is painful and complex, and poetry is the perfect form (in my opinion) to explore painful and complex emotions. Poems do not seek to provide answers, but to ask questions. Poems are not built around argumentation; they are built around emotions and ambivalence.

Mistress is a powerful testament to how art can help us to carry and hold the painful legacy of slavery in America and how poetry especially can help us to recover and access those whose lives were, and continued to be, affected by that legacy. These poems ‘sever the silence’ around Sally’s life and allow us into her world. Her loves, her desires, her choices, and her regrets. In short, her humanity.

Window at Monticello

Recommended Reading

Non-Fiction:

– The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon-Reed

– Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy by Annette Gordon-Reed

– Jefferson’s Daughters: Three Sisters, Black and White, in a Young America by Catherine Kerrison

– ‘Jefferson’s Monticello Makes Room for Sally Hemings’ from National Public Radio, June 2018

– Monticello itself has many resources online which are a great place to start learning more about Sally and her family. You can start with their ‘Slavery at Monticello’ general page or check out ‘The Life of Sally Hemings’. I’d of course recommend a trip to Monticello as well, if you’re anywhere nearby.

– Getting Word Oral History Project (Monticello’s oral history project for collecting stories and interviews with descendants of Monticello’s African American community)

Fiction exploring experiences of enslaved characters:

– Beloved by Toni Morrison

– Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson (and her entire Seeds of America trilogy, which are all for Young Adult readers)

– The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Related posts on this blog:

– Notes from Monticello II: Trying on Stays (blog about the experience of trying on replica 18th century corsets with Chet’la Sebree during my fellowship at Monticello)

‘Madeira Mondays’ is a series of blog posts exploring Early American history and historical fiction. I’m not a historian, but an author and poet who is endlessly fascinated by this time period. I am also currently writing/researching a novel set during the American Revolution and recently finished a Doctorate of Fine Art looking at how creative writers access America’s eighteenth-century past. Follow the blog for a new post every Monday.