In last week’s post, I shared part-one of my poem ‘The First Afflicted Girl’, from my upcoming poetry pamphlet Anastasia, Look in the Mirror. This week, I wanted to look more closely at the story behind the poem. And I don’t just mean the historical story that inspired it, but also how I wrote the poem itself. But first: if you’ve not read last week’s post, you might want to take a look at that one first and have a wee read of the poem (this post will probably make more sense if you do!).

‘The First Afflicted Girl’ is a persona poem. A ‘persona poem’ is a poem that adopts the voice of a specific character (maybe a historical character, a fictional character, etc.). In this case, the poem adopts the voice of Betty Parris who was one of the ‘afflicted children’ during the Salem Witch Trials, who accused others of being witches. Her short entry on Wikipedia says that she, alongside her cousin Abigail, ’caused the direct death of 20 Salem residents: 19 were hanged…(one) pressed to death.’ But Betty was a child – can we really say she caused those deaths? A nine-year-old child didn’t hang those women, a community did. What I’m saying is, that’s pretty harsh, Wikipedia!

But, nevertheless, Betty played a key role in this tragic episode, and several years ago I became curious about her life after reading A Delusion of Satan by Frances Hill (a very gripping nonfiction account of the Salem Witch Trials). Hill describes Betty as ‘impressionable’ and ‘steeped in her father’s Puritan theology that made terrifying absolutes of good and evil, sin and saintliness and heaven and hell.’ Hill also writes that: ‘Unsurprisingly, (Betty) was full of anxiety.’ These descriptions drew me to her, perhaps because ‘anxious’ and ‘impressionable’ were probably two words that could have been used to describe me as a kid, alongside imaginative (we’ll get to imagination in a moment).

Who was Betty?

For starters, Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Parris was the daughter was the daughter of Salem Village Reverend Samuel Parris. In 1692, she lived in Puritan Massachusetts in her father’s home with her eleven year old cousin Abigail (who plays a part in my poem). She also lived with an enslaved couple of Caribbean origins, Tituba and John Indian. It was unusual for a New England family at the time to keep slaves, and, at least from Hill’s account, it seems that Tituba was a constant presence in Betty’s life (maybe even more so than her mother, who I chose to make absent entirely from my poem). Betty would have known Tituba since infancy. It’s impossible to know the complex dynamic between little Betty and Tituba, but both Betty and Abby were certainly dependent on her – which is why Tituba’s presence is woven subtly throughout the poem. She’s always there, usually doing household chores to keep the home running (in part-one, for instance, she’s blowing air from the bellows into the fire).

What was Betty’s life like?

The days were quite monotonous for young Puritan children. Endless chores (sewing, helping with the cooking, spinning etc.). Families were mostly self-reliant (making many items there at home, like candles and clothes). Hill writes about how there was ‘little play or amusement’ for kids and, as they grew older, no entertainment or hobbies. The only books they had were religious ones. Most strikingly to me, there were few outlets for the little girls to imagine. Hill writes:

Young women of that time and place had nothing to feed the imagination, to expand understanding or heighten sensitivity. There were no fairytales or stories to help order and make sense of experience. Were was no art or theatre (…) boys enjoyed hunting, trapping, and fishing, carpentry and crafts. For girls there were no such outlets for animal high spirits or mental creativity.

This made me wonder: what would it have been like to be a little girl like Betty? What might the mind conjure up, if you had no outlet for your imagination? What might I have done, if I had been born in this environment?

So how did that research contribute to the poem?

The monotony of Betty’s existence is something I wanted to convey with the language of the poem, which uses frequent repetition (‘days and days and days/of lighting fires’). And if a young girl like Betty were to feel anything but content with these days of boredom and drudgery, then they would probably have interpreted these feelings as sinful and wicked. That’s why I bring in Betty’s repeated thoughts: ‘I am not wicked/I do not want to be wicked.’ These lines come immediately after she talks about ‘wanting/to be in bed instead of/sewing, washing, sweeping.’ ‘I do not want sunshine’, she tries to assure herself, but already, from a few stanzas back, we know that she ‘dream(s) her cheeks are burned by sunlight’.

A few lines later, when Betty says the ‘outside is not different/from the in’, that line refers to the house being dark inside and out because it’s the dead of winter. But, on another level, it’s also her hope that her internal world and what she presents outwardly are the same. Of course, they’re not the same. Inside, it’s tumultuous and full of conflicting desires and self-chastisement, even if on the ‘outside’ she’s playing the part of an obedient child who doesn’t ‘want sunshine’.

The final three lines of part-one, ‘We burn the candles/and keep them/burning’, also works on two levels (I hope!). This is a physical description of the setting meant to convey just how dark it was during those bleak winter months, but also ending that section on the word ‘burning’, and isolating the word like that, on its own line, is suggestive of the witch trials that are to come (keep them burning). Although no women or men were burned alive in Salem, this imagery does evoke witch trials generally, I think. It’s a sinister note to end on, suggesting bad things to come, and the poem definitely takes a turn for the increasingly more sinister and strange in parts two and three, as Betty becomes more physically, emotionally and psychologically distressed. In the poem, as in life, she begins speaking incoherently, having violent convulsions, and eventually causing everyone around her to conclude that she has been ‘bewitched’.

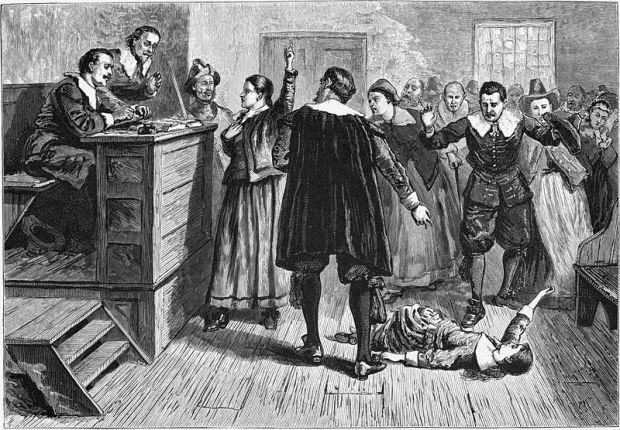

‘Witchcraft at Salem Village’ engraving from 1876, accessed here

*

Of course, each reader will get something different from the poem, and just because I intended for something to be read a certain way, that doesn’t mean that it will be! Overall, in the first section, I really wanted to convey Betty’s fear of being ‘wicked’, the physical discomforts of her life, and the fervent religion beliefs of her time. Section two explores Betty’s dabbling with fortune telling (and her increasingly morbid thoughts) and finally her descent into ‘hysteria’. My poem ends before the Witch Trials actually begin. (I won’t say exactly how it ends! For that, you’ll need to read the full poem in the book!)

In reality, what happened was that Betty and Abby accused three (vulnerable) women of being witches: Sarah Good, a homeless woman; Sarah Osborne, an elderly impoverished woman and (perhaps most tragically and most predictably) the woman who had cared for them, Tituba.

Tituba survived, but many people did die as a result of the ensuing witch trials (nineteen hanged and one man pressed to death). I don’t have an answer as to ‘why’ the real historical Betty behaved the way she did. There were probably numerous contributing factors that led to her odd behavior. There are certainly many factors that led to the Salem Witch Trials generally, including long-standing superstitions (witch trials had been going on in Europe for years) and complex relationships and rivalries between members of Salem Village and Salem Town. As for the girls’ affliction: there’s a theory (put forward by psychologist Linnda Caporael in the 1970’s) that blamed their abnormal behavior on the fungus ergot, which can be found in rye and might have caused hallucinations. But this theory is not really supported by historians, as explained very well in this blog post from a history student and tour guide in Salem.

In any case, my poem is not trying to explain exactly what happened to the girls, and it’s certainly not delving into the complex origins of the trials themselves. What I am trying to do is explore a certain state of being, a state of boredom, fear and anxiety that might have taken hold of this ‘impressionable’ nine-year-old girl. Hill also notes, and I agree with this argument, that this is a time when women weren’t allowed any sort of public voice, and had little to no power in their homes, so even feigning this kind of ‘affliction’ would have given the girls a kind of power. People would have listened to them, taken them seriously, an intoxicating prospect for a Puritan girl, even if it had deadly consequences.

Examination of a Witch (1853) by T.H. Matteson, accessed via Wikipedia

*

Within my book, this poem is also positioned right before a poem about my own experience of ‘Abstinence Only’ sexual education in a Texas public high school, very much an anxiety-inducing experience and one more aimed, in my experience, at scaring young people than educating them. Through this ordering of poems, I’m trying to draw (unsettling) parallels between past and present, and to raise questions about how young people are ‘educated’ then and now.

So that’s a bit of insight into the research and thinking behind this poem! (There are much cheerier poems in the pamphlet too, I should add! The aforementioned ‘Sex Ed’ poem is actually really funny – I hope!). If you’d like to read more, the whole poem is in Anastasia, Look in the Mirror (available for pre-order here).

And if you’d like to learn more about Salem generally, here are a few ideas:

Recommended Further Reading/Listening/Viewing:

Books:

- This article on Book Riot lists lots of good historical fiction and non-fiction about Salem

- Mary Beth Norton is one of the go-to historians on this topic, so you could try her book In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692

- A Delusion of Satan by Frances Hill (This is the main account I read when I was writing this poem several years ago. It’s an engaging book, but Hill isn’t an early American historian, so I’d say to complement it with another book!)

Movies:

- The Witch directed by Robert Eggers (one of my favorite films! I wrote about it last Halloween here)

Podcasts:

- Ben Franklin’s World Episode 53: Emerson W. Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft (a fascinating interview with a historian/archeologist about what happened in Salem)

‘Madeira Mondays’ is a series of blog posts exploring Early American history and historical fiction. I’m not a historian, but an author and poet who is endlessly fascinated by this time period. I am also currently writing/researching a novel set during the American Revolution and recently finished a Doctorate of Fine Art looking at how creative writers access America’s eighteenth-century past.

Follow the blog for a new post every Monday and thanks for reading!

Another fascinating and absorbing post!! Thank you for taking the time to write this for us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! I’m glad that you found it interesting! It was fun to reflect back on the writing process and what went into the poem. Thanks for your comment! x

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome! I really enjoy reading your posts!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 😀 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person